Prologue

This is an article that I originally wrote for Forensic Magazine back in 2011. For whatever reason Forensic Mag decided to take it down so I then archived it to ResearchGate. Although some of the content is dated, my hope is to continue to add to this “living Blog document” of sorts until the opportunity arises to publish this work in an academic journal in the near future for posterity’s sake.

Introduction

With the field of digital forensics growing at an almost warp-like speed, there are many issues out there that can disrupt and discredit even the most experienced forensic examiner. One of the issues that continue to be of utmost importance is the validation of the technology and software associated with performing a digital forensic examination. The science of digital forensics is founded on the principles of repeatable processes and quality evidence. Knowing how to design and properly maintain a good validation process is a key requirement for any digital forensic examiner. This post will attempt to outline the issues faced when drafting tool and software validations, the legal standards that should be followed when drafting validations, and a quick overview of what should be included in every validation.

Setting the Standard

#DFIR Thought of the Day: It should be of utmost importance that we all continue to look to develop the scientific foundations for the practice of digital forensics, including standardization of our tool outputs & results.

— Josh Brunty (@joshbrunty) August 25, 2021

Standards and Legal Baselines for Software/Tool Validation

According to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), test results must be repeatable and reproducible to be considered admissible as electronic evidence. Digital forensics test results are repeatable when the same results are obtained using the same methods in the same testing environment. Digital forensics test results are reproducible when the same when the same test results are obtained using the same method in a different testing environment (different mobile phone, hard drive, and so on). NIST specifically defines these terms as follows:

Repeatability:

refers to obtaining the same results when using the same method on identical test items in the same laboratory by the same operator using the same equipment within short intervals of time.

Reproduciblity:

refers to obtaining the same results being obtained when using the same method on identical test items in different laboratories with different operators utilizing different equipment.

In the legal community, the Daubert Standard can be used for guidance when drafting software/tool validations. The Daubert Standard allows novel tests to be admitted in court, as long as certain criteria are met. According to the ruling in Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals Inc. the following criteria were identified to determine the reliability of a particular scientific technique:

- Has the method in question undergone empirical testing?

- Has the method been subjected to peer review?

- Does the method have any known or potential error rate?

- Do standards exist for the control of the technique’s operation?

- Has the method received general acceptance in the relevant scientific community?

The Daubert Standard requires an independent judicial assessment of the reliability of the scientific test or method.This reliability assessment, however, does not require, nordoes it permit, explicit identification of a relevant scientificcommunity and an express determination of a particular degree of acceptance within that community. Additionally, the Daubert Standard was quick to point out that the fact that atheory or technique has not been subjected to peer review orhas not been published does not automatically render thetool/software inadmissible. The ruling recognizes that scientific principles must be flexible and must be the product of reliableprinciples and methods. Although the Daubert Standard was inno way directed toward digital forensics validations, thescientific baselines and methods it suggests are a good startingpoint for drafting validation reports that will hold up in a court of law and the digital forensics community.

While it’s true Best Practices (like those SWGDE, OSAC, & ASTM) are not concrete standards per-se, they are practices that are produced, agreed upon, and practiced by professionals in the scientific community. Both Frye & Daubert Challenges focus on the application of.. (1/3)

— Josh Brunty (@joshbrunty) July 8, 2021

The Scientific Method and Software/Tool Validations: A Perfect Fit?

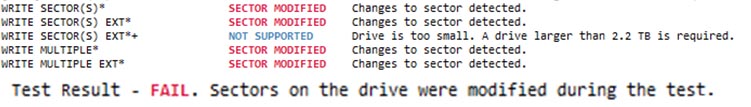

In the Daubert ruling, The Court defined scientific methodology as “the process of formulating hypotheses and then conducting experiments to prove or falsify the hypothesis.” The Scientific Method refers to a body of techniques for investigating phenomena, acquiring new knowledge, or correcting and integrating previous knowledge. To be termed scientific, the method must be based on gathering, observing, or investigating, and showing measurable and repeatable results. Most of the time, the scientific process starts with a simple question that leads to a hypothesis, which then leads to experimentation, and an ultimate conclusion. To exemplify, if you are validating a particular hardware write blocking device you may want to start with the simple question “Does this tool successfully allow normal write-block operation to occur to source media?” Since it is assumed that the write-blocking device supports various types of media (SATA, IDE, and so on) you may be required to list the various requirements of the tool. Because if this, it is good practice for an examiner to use the scientific method as a baseline for formulating digital forensic validations. It is recommended that forensic examiners follow these four basic steps as a starting point for an internal validation program:

1) Develop the Plan

Developing the scope of the plan may involve background and defining what the software or tool should do in a detailed fashion. Developing the scope of the plan also involves creating a protocol for testing by outlining the steps, tools, and requirements of such tools to be used during the test. This may include evaluation of multiple test scenarios for the same software or tool. To illustrate, if validating a particular forensic software imaging tool, that tool could be tested to determine whether or not it successfully creates, hashes, and verifies a particular baseline image that has been previously setup. There are several publically available resources and guides that can be useful in establishing what a tool should do such as those available from NIST’s Computer Forensic Tool Testing Project (CFTT) available from http://www.cftt.nist.gov. The CFTT also publishes detailed validation reports on various types of forensic hardware and software ranging from mobile phones to disk imaging tools. In addition to CFTT, Marshall University has published various software and tool validation reports that are publically available for download from http://forensics.marshall.edu/Digital/Digital-Publications.html. These detailed reports can be used to get a feel for how your own internal protocol should be drafted. The scope of the plan may also include items such as: tool version, testing manufacturer, and how often the tests will be done. These factors should be established based on your organization standards. Typically, technology within a lab setting is revalidated quarterly or biannually at the very least.

2) Develop a Controlled Data Set

This area may be the longest and most difficult part of thevalidation process as it is the most involved. This is because it involves setting up specific devices and baseline images andthen adding data to the specific areas of the media or device. Acquisitions would then need to be performed and documentedafter each addition to validate the primary baseline. This baseline may include a dummy mobile phone, USB thumbdrive, or hard drive depending on the software or hardware tool you are testing. In addition to building your own baseline images, Brian Carrier has posted several publically availabledisk images designed to test specific tool capabilities, such asthe ability to recover deleted files, find keywords, and processimages. These data sets are documented and are available athttp://dftt.sourceforge.net. Once baseline images are created,tested, and validated it is a good idea to document what is contained within these images. This will not only assist in future validations, but may also be handy for internal competency and proficiency examinations for digital examiners.

3) Conduct the Tests in a Controlled Environment

Outside all the recommendations and standards set forth by NIST and the legal community, it only makes sense that a digital forensics examiner would perform an internal validation of the software and tools being used in the laboratory. In some cases these validations are arbitrary and can occur either in a controlled or uncontrolled environment. Since examiners are continuously bearing enormous caseloads and work responsibilities, consistent and proper validations sometimes fall through the cracks and are validated in a somewhat uncontrolled “on-the-fly” manner. It’s also a common practice in digital forensics for examiners to “borrow” validations from other laboratories and fail to validate their own software and tools. Be very careful with letting this happen. Keep in mind that in order for digital forensics to be practicing true scientific principles, the processes used must be proven to be repeatable and reproducible. In order for this to occur, the validation should occur within a controlled environment within your laboratory with the tools that you will be using. If the examiner uses a process, software, or even a tool that is haphazard or too varied from one examination to the next, the science then becomes more of an arbitrary art. Simply put, validations not only protect the integrity of the evidence, they may also protect your credibility. As stated previously, using a repeatable, consistent, scientific method in drafting these validations is always recommended.

4) Validate the Test Results against Known and Expected Results

At this point, testing is conducted against the requirements set forth for the software or tool in the previous steps. Keep in mind that results generated through the experimentation and validation stage must be repeatable. Validation should go beyond a simple surface scan when it comes to the use of those technologies in a scientific process. With that said, it is recommended that each requirement be tested at least three times. If there are any variables that may affect the outcome of the validation (e.g. failure to write-block, software bugs) they should be determined after three test runs. There may be cases, however, where more or fewer test runs may be required to generate valid results. It’s also important to realize that you are probably not the first to use and validate a particular software or tool, so chances are that if you are experiencing inconsistent results, the community may be experiencing the same results as well. Utilizing peer review may be a valuable asset when performing these validations. Organizations such as the High Technology Crime Investigation Association (HTCIA) and the International Association of Computer Investigative Specialists (IACIS) maintain active member e-mail lists for members that can be leveraged for peer review. There are also various lists and message boards pertaining to mobile phone forensics that can be quite helpful when validating a new mobile technology. In addition, most forensic software vendors maintain message boards for software, which can be used to research bugs or inconsistencies arising during validation testing.

Conclusion

Real world laboratory use, controlled internal tests utilizing scientific principles, and peer review should all be leveraged in a validation test plan. Sharing unique results with the digital forensics community at-large helps investigators, examiners, and even software and tool vendors ensure that current best practices are followed. As the field of digital forensics continues to grow and evolve as a science the importance of proper scientific validation will be more important than ever.

References

- Brown, C. “Computer Evidence: Collection & Preservation.” Hingham: Thomson/Delmar. 2006.

- Carrier, B. “Digital Forensics Tool Testing Images.” Accessed 06 Feb 2011. http://dftt.sourceforge.net/.

- Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, 509 U.S. 579 (1993).

- High Technology Crime Investigation Association, Accessed 06 Feb 2011. www.htcia.org.

- International Association of Computer Investigative Specialists, Accessed 06 Feb 2011. www.iacis.org.

- Maras, MH. Computer Forensics: Cybercriminals, Laws, and Evidence. Sudbury: Jones & Bartlett. 2011.

- Marshall University Forensic Science Center-Digital

Publications, Accessed 06 Feb 2011.

http://forensics.marshall.edu/Digital/DigitalPublications.html.

-

- NIST Computer Forensic Tool Testing Project. Accessed 06 Feb 2011. www.cftt.nist.gov.

-